San Pancrazio is a 7th century minor basilica and parish and titular church, just west of Trastevere at Piazza San Pancrazio 5/D. This is in the suburb of Monteverde Vecchio, part of the Gianicolense quarter. Pictures of the church at Wikimedia Commons are here. There is an English Wikipedia page here.

The church is up a driveway from the road, and is surrounded by the park of the Villa Doria Pamphilj.

The dedication is to St Pancras.

History[]

Saint[]

The basilica is on the site of the tomb of St Pancras , an early 4th century martyr. Unfortunately his legend is unreliable, but his veneration is in evidence from early times. The revised Roman martyrology carefully states in its entry for 12 May: "St Pancras, martyr and young man who by tradition (fertur) died at the second milestone on the Via Aurelia". The actual location is on the present Via Vitellia, which is possibly an ancient road in its own right.

The legend alleges that the body of the martyr was interred by a pious woman called Octavilla. This detail is thought to preserve the name of the proprietor of the cemetery in which the martyr was buried, which as a result is also called the Catacombe di Ottavilla.

The re-laying of the church's floor in 1934 revealed some of the original surface cemetery (cimitero all'aperto), which began as a pagan burial ground in the 1st century. Three columbaria or "gardens of remembrance" for funerary ashes were found. This cemetery around the saint's tomb was extended as a Christian catacomb beginning at the start of the 4th century, with four separate identifiable foci. The earliest area seems to be contemporary with his martyrdom.

It is postulated, without confirmatory archaeological evidence, that a small shrine building existed here from the early 4th century because the Martyrologium Hieronymianum entry (thought to derive from the 5th century) lists the dies natalis or festal celebration of the martyr here on 12 May.

First church[]

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Pope St Symmachus (498-514) built a basilica on the site of the oratory. He also had a hospice for pilgrims built adjacent to it, and the complex was put into the charge of the secular clergy of the old titular church of San Crisogono. Also provided was a balneum, which is often taken to refer to a baptistery but actually means a "bath". This might not have been a baptismal font but a healing shrine, as at Lourdes nowadays.

Early pilgrimage itineraries mention an odd fact concerning the saint's shrine in the church -it was either off to one side in the building or at an angle to its axis -ex obliquo aulae, according to the Einsiedeln Itinerary for example. The Latin can mean either. This is taken as evidence that the martyr was buried on the surface, and that the church plan had to respect other pre-existing structures (most likely mausolea) when it was built over his undisturbed tomb.

St Gregory of Tours (538-94) wrote that the shrine was being used as an ordeal, with those suspected of false oaths being asked to repeat their allegations in front of it. It was believed that those persisting in lies would then suffer horrible results -"snatched by a demon or struck dead".

Foundation of monstery[]

Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) preached an extant homily here (his twenty-seventh), witnessing to the popularity of the shrine and the occurrence of miracles of healing (in the balneum?). By his time the ancient Porta Aurelia had been renamed Porta San Pancrazio in the saint's honour.

The same pope also wrote an extant letter to the abbot of an adjacent monastery which he had founded after dispossessing the chapter of San Crisogono (Book IV, number 18, translation by John Martyn):

"Gregory to Maurus, abbot of St Pancras, March 594.

The care of churches, which has already been established among priestly duties, forces us to be very much concerned that no fault of neglect should appear in them. But we have learned that the church of St Pancras, which was entrusted to priests, has frequently suffered from neglect to the extent that, when the people came on a Sunday to celebrate solemn Mass, the found no priest and returned home muttering. And so, after due deliberation, we have settled on this decision. We should remove the priests and establish a community of monks in the monastery attached to the same church, by the grace of Christ, so that the abbot in charge there should have total care and concern for the aforesaid church.

We have decided that you, Maurus, should be put in charge as abbot of that monastery. And we make it a condition that the lands of the aforesaid church, and whatever has entered there or has accrued from its financial returns, ought to be directed to the aforesaid monastery of yours, and should apply there without any reduction. In this way, of course, whatever needs to be done and repaired in the church should, without doubt, be repaired thorough you.

But, in case that church might seem to lack the holy mysteries, when the priests have been removed to whom the church has been entrusted before, we accordingly order you, with the direction of this authority, not to stop employing the peregrinus priest there, who could celebrate the holy solemnities of Mass. However, it is necessary that he should both live in your monastery and obtain his sustenance from there. But take care over this, before all else, that each day the Work of God is carried out there without question, before the most sacred body of St Pancras. And so we consider that you should do these things through the direction of this order. We not only want you to carry them out, but we also want them to be preserved and implemented in perpetuity by those who succeed you in office and rank, so that no neglect might be found thereafter in the above-mentioned church."

Pope Gregory was himself a monk, and had a low opinion of the quality of the Roman clergy. This is one instance of his favouring his fellow monastics over secular priests in administrative duties. An interesting point is that the monks here were not ordained but had to rely on an expatriate (peregrinus) priest for the provision of Mass at the church.

Note that the letter says nothing about what sort of rule of life the monks followed. From the 10th century it was alleged that he staffed the new monastery with Benedictine monks who had been expelled from Montecassino in the year 528. However, this story is nowadays regarded as unhistorical by serious historians. (It is still, unfortunately, widely quoted.) The alleged association of Benedictines with Roman monasticism from the 6th century was actually a malicious fabrication, which airbrushed out of history the dominance at Rome of refugee and expatriate monks from the eastern Mediterranean in the 7th and 8th centuries. The fabrication furthered the interests of Benedictine reformers from the 10th century, and polemicists involved in the Great Schism of 1054.

Early monastery[]

Pope Gregory's policy of favouring monks over secular clergy was resented, and was reversed after his death. Although specific documentary evidence is lacking, it is clear that the pope's intention was overturned which foresaw that the monastery should have permanent charge of the church. The clergy of San Crisogono in Trastevere recovered their lost property, and the monastery became a separate institution.

The ownership by San Crisogono was not abolished until 1205. This seems to explain why the monastery here later had a dedication to St Victor, not to St Pancras -the monks were not in charge of the martyr's church, although they almost certainly provided the liturgical singing. The first mention in genuine historical records of the monastery after the letter of Pope Gregory is from the reign of Pope Adrian I (772-95), who restored both shrine and monastery. The latter was already named after St Victor.

However, in this pope's reign there was another monastery dedicated to St Pancras next to the Lateran. This convent might have derived its dedication from the tradition that the saint had lived nearby, on the Coelian Hill. Alternatively, and more likely, it was founded because of a papal devotion to the saint. It was usefully co-opted into the Benedictine foundation myth as the place where the monks of Montecassino settled when they arrived at Rome in 528, but is only known to have existed historically in the early 8th century. The location was apparently where St John Lateran's sacristies are now.

Pilgrimage destination[]

From the 6th century, the shrine was firmly on the suburban pilgrimage circuit. Pilgrims setting out on the Via Aurelia came to San Pancrazio first, near which was the Catacomba dei Santi Processo e Martiniano. Going on a little further on the main road, they came to the Catacomba dei Due Felici and then the Catacomba di Calepodio. "Ultras" could carry on for another nine miles to the Catacomba di San Basilide if they were keen enough. Obviously some were, for the place to be mentioned at all.

As well as St Pancras, visiting mediaeval pilgrims could also descend into the catacombs and venerate the martyrs SS Artemius and Paulinus, also St Sophia with her three daughters Fides, Spes and Caritas. The first two are completely obscure, and the quartet is thought to be a fiction derived from an allegorical sermon because their names are "Wisdom, Faith, Hope and Charity". It does not improve matters that a rival quartet with the same names was in the Catacombe di San Callisto.

Second church[]

Pope Honorius I (625-638) rebuilt the basilica. There is some disagreement between sources -the Liber Pontificalis entry has the rebuilding done "from the foundations". Further, Armellini in his Archeologia Cristiana 1898 transcribes the alleged mosaic epigraph provided by the pope which proclaims this:

Ob insigne meritum et singulare beati Pancratii martyris beneficium, basilicam vetustatem confectam extra corpus martyris neglectu antiquitatis, extructam Honorius episcopus Dei famulus, obruta vetustatis mole ruinamque minante, a fundamentis noviter plebi Dei construxit et corpus martyris quod ex obliquo aulae iacebat altari insignibus ornatu metallis, proprio loco collocavit.

However, a mediaeval transcription of an ancient inscription now at the library of Einsiedeln Abbey describes the church as rebuilt "for the most part". This indicates that at least the original foundations were used, and some hope has been expressed that fabric from the first church can be found in the present building. This hope has not been realised, as the only certain survivals are re-used column bases in the sanctuary arcades.

The arcades of the new church were supported on a set of ancient grey granite columns, some of which survive but not in the present nave.

Pope Honorius provided a confessio or sanctuary crypt, and enshrined the relics of the martyr in it. The new shrine was below the high altar (as the epigraph quoted hints at). The Liber Pontificalis records that 287 pounds of silver went into the shrine canopy.

9th century[]

The present basilica is basically the result of the rebuilding by Pope Honorius, albeit with such thorough remodelling that its age is not immediately obvious to the visitor.

In the 9th century, rather unusually, nothing of a radical nature happened here. The city lost control of its hinterland in that century to various marauders and raiders, including Muslim ones, so the Church undertook a systematic and rather costly project to strip and abandon most of the catacombs and suburban shrines. The relics of the martyrs were transferred to churches within the city walls, many of which were remodelled for the purpose.

However, here St Pancras was mostly left in place and his shrine remained a pilgrimage destination for the entire Middle Ages. The head of the saint only was removed from the set of relics and taken to St John Lateran, which proved fortunate.

The catacombs ceased to be visited, however, as the saint was accessible in his church crypt. This is in contrast to San Sebastiano fuori le Mura, where the catacombs never ceased to be a visitor attraction (the only Roman set never to have been shut down). To be fair, it has been claimed that graffiti in the so-called "Region K" demonstrates mediaeval visits, but the writer hasn't seen the evidence.

This 9th century retrenchment caused the abandonment and loss of the other catacombs on the Via Aurelia. These were genuinely forgotten, so that the Catacomba di Calepodio were mistakenly identified with the ones here. This mistake became influential in the late 16th century, and is still to be found in print. Antonio Bosio went looking for the Calepodian cemetery then, failed to find it and so came to this erroneous conclusion.

Later monastery[]

In 1061 is the first genuine reference to a Benedictine monastery here, under the authority of the great French abbey of Cluny. However, San Crisogono remained in immediate charge of the shrine until Pope Innocent III cancelled its authority in 1204. In that same year, he crowned King Peter II of Aragon in the basilica.

This was one of the twenty Benedictine abbeys in the city in the 11th century, the abbots of which had an important role in papal ceremonies. Its rank in the pecking order was number seven.

An abbot called Hugh (Ugone in Italian) commissioned a re-ordering of the interior from 1244, including the provision of two notable Cosmatesque ambones (pulpits) and a paschal candlestick. He also oversaw the installation of a floor and a sanctuary screen in the same style. The Gospel ambo was embellished with spiral colonnettes and an eagle, and had a mosaic dedicatory inscription with the date 1249. The plainer Epistle ambo was dated 1244. The candlestick was fluted, with a Corinthian capital. All of this work was destroyed at the start of the 19th century, with sad fragments surviving including of the inscriptions.

Nunnery[]

Despite this expensive work the Benedictine abbey only lasted until 1255, when the black monks abandoned the complex and left it in the hands of the pope. The circumstances of the collapse are completely obscure. The observance in Benedictine monasteries at Rome had fallen into disgraceful corruption from the late 12th century, and the order lost them all as a result -except for San Paolo fuori le Mura. The Franciscans were the major beneficiaries of this collapse elsewhere -for example, at Santa Maria in Aracoeli.

Here, in December of that year Pope Alexander IV granted the vacated complex to a nascent community of Cistercian nuns, who were based at Santa Maria sopra Minerva and who had evolved from an informal commune of repentant prostitutes. The nuns formally joined the Cistercian order only in 1271. The nunnery adopted the dedication of Santa Maria e San Pancrazio, as the Cistercian tradition is that all their churches are dedicated to Our Lady.

The nunnery initially flourished, and in about 1320 was listed as having thirty-five nuns. However, in the next century something rather odd happened because the abbess swapped their church and convent for that at San Pietro in Montorio in 1438. The new incumbents were the Augustinian Congregation of St Ambrose, also known as Ambrosians or Ambrosiani.

The nuns did not flourish in their new home -they were extinct in a couple of decades.

Ambrosiani[]

The Ambrosians were a Milanese foundation, formally known as the Congregatio Sancti Ambrosii ad Nemus because they had been founded in a wood outside the city in 1375. San Pancrazio was treated as a dependent house of their main monastery in Rome at San Clemente

The church was restored on the orders of Sixtus IV (1471-84) after it had become ruinous. This involved walling up the nave and transept arcades and abandoning the side aisles and chapels. It is thought that the right hand central nave wall was mostly rebuilt, as was the façade. The ancient arcade columns were mostly left in situ, embedded in the new walls.

(It should be noted here that an alternative theory suggests that the conversion to a single nave was undertaken for the nuns in 1255.)

The Ambrosian convent was obviously, in its turn, already in serious decay. It was finally suppressed in 1517, when the church was made titular, and that was the end of any monastic presence here.

Dall'Ugonio wrote a valuable description when he visited the church in 1565. At this time the layout resembled that of San Vitale -a single nave leading into an apse.

17th century restorations[]

Being titular was not just an honorific attached to a church, because the idea was that the cardinal would spend his own funds on keeping it in repair. This wan't mandatory so didn't always work -but a cardinal who allowed his church to remain in poor repair would have damaged his reputation.

In 1606 a major restoration was finally undertaken of the mutilated basilica on the orders of Cardinal Ludovico de Torres (his memorial is in the church) with the help of his nephew Cosimo. The side aisles were re-roofed and their arcades unblocked. Early Baroque details were added to the interior, and the present façade built. The relics of St Pancras were brought up from the crypt and enshrined under the high altar. Six separate carved wooden ceilings were provided for the central nave (which did not have one before), the sanctuary with its chapels and the side aisles.

The restoration was terminated in 1609 with the death of the cardinal. Apparently some details were abandoned, such as the painting and gilding of the ceilings.

Unfortunately, the set of ancient arcade colonnade columns was scattered. Three are free-standing outside (you passed one coming up the drive), two are flanking the main entrance door and one was re-used as an Easter candlestick. Apparently one stands outside San Francesco d'Assisi a Ripa Grande and others are in the Casino of the Villa Doria Pamphilj.

This was the point at which interest reawakened as regards the catacombs under the church.

In 1662 the church was entrusted by Pope Alexander VII to the Discalced Carmelites, who set up a friary here and are still in charge of the parish. They immediately commissioned an embellishing of the interior with stucco decorations in Baroque style, as well as a fresco in the apse conch (now destroyed).

19th century[]

The 19th century was not kind to the church. Firstly it was thoroughly looted by the French in 1798, with valuable fittings being stolen including the polychrome marble work. It is recorded that the relics of the saint were desecrated and scattered about, but apparently most of him was rescued afterwards.

As a result of the sack the church was left derelict until the formal restoration of papal government in 1815.

It was then partially destroyed again by the Garibaldians during their futile defence of the Roman Republic against the French army in 1849. This vandalism included having the shrine broken open again and the relics of the martyr disposed of. Whatever the vandals did with them, whether they put them down the toilet or shot them from a cannon, it is the case that not even a fragment was recovered.

A contemporary description describes the church's interior walls left with "blasphemous inscriptions, vile caricatures and indecent sketches".

As a result of the loss of the relics, when substantial necessary repairs were carried out to the church in the mid 19th century and the altar reconsecrated, a small portion was brought back from the head of the saint at St John Lateran to be enshrined under the high altar.

20th century[]

The roof was repaired in 1909. The catacombs were investigated properly, and had their fabric consolidated, in 1924.

The church was made parochial in 1931, after major suburban development had occurred on the other side of the road. This triggered another restoration in 1934, including the re-laying of the floor which gave an opportunity for archaeological investigations. This revealed the original 1st century cemetery, but did not find the original shrine.

In 1954, the Discalced Carmelite theological college known as the Teresianum moved into very ample facilities next door, just to the west. Also, the Figlie di Santa Maria della Divina Provvidenza established their Generalate or congregational headquarters behind the church's convent. This is now a nursing home called the Casa San Pio X.

In 1959 there was a restoration of the sanctuary area including the provision of a new baldacchino using old materials, and some frescoes were added to the interior walls. The critical response to the latter has been rather hostile (scarso valore artistico). It was unfortunate that the apse conch fresco by Luigi Ciotti entailed the destruction of its 17th century predecessor.

In 1973, Blessed Pope Paul VI ordered the rest of the head of the saint to be transferred from the Lateran to be enshrined here.

Nowadays[]

The church remains the home of an active parish, but it has to be admitted that St Pancras is not the focus of much pilgrimage interest nowadays.

After a long period of casual access ("ask a friar"), a passage roof fall forced the closure of the catacombs for safety reasons in 2001. However, after consolidation they have recently been opened to the public again as a parish initiative. This is to be commended, and deserves support. The scheme seeks to raise funds for charities helping poor people in Rome.

St Pancras in England[]

The myth of Benedictine monks being here under Pope St Gregory the Great had an odd outcome in English transport history.

Pope Gregory sent a mission to barbarian England in 597, under the authority of St Augustine of Canterbury. He established his bishopric at Canterbury, and founded a monastery at the start of the 7th century with a main church dedicated to SS Peter and Paul. This monastery originally had at least two other churches, and the ruins of one survive which was dedicated to St Pancras. It is unknown how the monastery functioned liturgically or pastorally (again, later claims of original Benedictine status have muddled the historical record), but the original tomb of the saint was functioning as a healing shrine at the time and this might have been the original status of the little church at Canterbury.

The monastery later became St Augustine's Abbey.

The great French Benedictine abbey of Cluny expanded its reform congregation into England after that country was conquered by the Normans in 1066, and the first monastery that it built in that country was at Lewes in Sussex. It was dedicated to St Pancras as well. The priory church was the largest church in Sussex.

One of the parish churches in the then outer suburbs of London, now called Old St Pancras, took the dedication when it was founded perhaps in the 10th century. The church passed the name on to a train station built next to it in the 19th century. This is now St Pancras International, and if you take a train from the European mainland to London this is where you will arrive.

Cardinalate[]

The first cardinal priest of the church was Ferdinando Ponzetti, appointed in 1517.

The present titular is Cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera.

Exterior[]

Approach[]

The church is approached through a 17th century Baroque gateway, over which is a faded fresco of the Crucifixion in an arched canopy supported by two little marble columns with vines twisting around them. This gateway would have replaced a mediaeval one, giving access through a defensive wall surrounding the monastery precincts which has now gone.

Fresco over gateway.

The coat of arms on the keystone below the fresco is of the family of the restorers of the church in 1606, Cardinals Ludovico and Cosimo de Torres (note the towers on the shield).

The driveway beyond the gate is surprisingly long. This would have passed through the outer court of the mediaeval Benedictine monastery, containing such departments as the stables, brewery and guest-house. It now passes a free-standing ancient grey granite column with a metal cross on top. This is allegedly from one of the original 7th century nave arcades. (Two other such columns stand on convent premises at the back, apparently.)

To one side of the church's entrance piazza is a Lourdes grotto which is a focus of parish devotion.

Layout[]

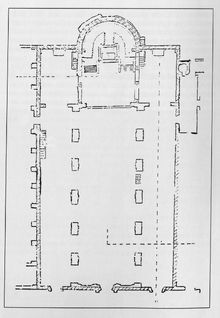

The church edifice is on a classical basilical plan, rectangular overall with a central nave and side aisles having six bays. There follows a transept of three shallower bays which is divided structurally into a sanctuary and a pair of side chapels and is divided from the nave and aisles by a transverse arcade of three arches. Finally there is an external semi-circular apse.

This is a large church, about 55 metres long.

Attached to the right hand side of the church is the Carmelite convent, arranged around a small square cloister which is virtually certainly on the footprint of the mediaeval monastic one. However, the latter was larger. The present cloister has arcades topped by upper-storey accommodation, whereas the mediaeval cloister walkways would have had pentise roofs. If you look at Google Earth, you will see how the cloister ranges are add-ons within the mediaeval cloister plan.

The left hand side of the church is occupied by a very narrow courtyard, and the wall here has an arcaded walkway. On the other side of the courtyard is a wing of the Teresianum. Apparently a third entrance to the catacombs is around here -the other two known ones are in the church.

Campanile[]

On the far side of the convent wing abutting the church's sanctuary is attached a 17th century tower campanile, in brick rendered in white. This has two storeys above the roofline, the first being blank-walled and the second having a large arched sound-hole on each face. The imposts of the arches are continued as a string-course. On top there is a roofline entablature, and a tiled cap from which protrudes a little lead cupola having a parabolic curve.

Fabric overview[]

The church contains substantial amounts of 7th century fabric, but exactly just how much is uncertain because it has never had its render completely stripped for a proper survey. This render is in a faded dark pink where the church's walls are not abutted by other structures.

The roofs of the central nave, aisles, transept and apse are pitched and tiled. The central gabled nave roof is slightly higher than the central gabled roof of the sanctuary, and the two single-pitched roofs of the transept side chapels are also slightly higher than the nave side aisle roofs.

The important thing to note about these roofs is that the tops of the side aisle and chapel roofs are only slightly lower than the gutters of the central nave and sanctuary roofs. This means that the central nave and transept side walls are concealed, whereas they were exposed and had windows in the earlier Middle Ages. The lack of windows means that the interior is short of natural light. The roofs have dormer windows, but these light the voids above the ceilings.

All this roofing is later 19th century.

What is 7th century?[]

The following summary of the ancient fabric depends on Matilda Webb: The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome 2001.

The 7th century fabric is in opus vittatum, alternating several courses each of brick and stone. It comprises the apse, the rear wall of the right hand side chapel with its return corner, all the walling of the left hand side chapel, the left hand aisle wall and left hand central nave wall.

It is thought that the transept was always divided into three zones, a central sanctuary and two self-contained side chapels, as it is now. This is based on the evidence of a wall containing an original round-headed window above the entrance arch of the right hand chapel (invisible because of the ceilings).

Originally, the apse had three round-headed windows which were partly blocked up at some stage to create three round ones and then later completely blocked. The central sanctuary walls, over the original roofs of the side chapels, had three large round-headed windows each. It is thought that each central nave wall had six smaller round-headed windows.

The right hand central nave wall is thought to be mostly 15th century, except for the portion in the first nave bay. An original window survives here, also hidden by the side aisle roof. The right hand side wall and façade are early 17th century rebuilds (it has been suggested that the latter is of 15th century fabric).

Façade[]

The very late (1606) Renaissance-style façade is simple, rendered in a faded dark pink with windows and door-cases in white marble. Unusually, there is no porch or loggia and this might have been because the money ran out in the early 17th century. The existence of an original atrium attached to the 7th century church, such as the surviving one at San Clemente, has been postulated but there is no archaeological evidence for it. The mediaeval church fairly certainly had a narthex or entrance porch of some sort, such as at San Giovanni a Porta Latina.

There are three doorways for nave and aisles. The fourth one on the extreme left leads into a courtyard, and apparently once gave access to a catacomb entrance. Note the inscription over it: Coemiterium sancti Calepodii presbyteri et martyris Christi. This gives witness to a centuries-old erroneous identification.

The main entrance door-case is larger, flanked by a pair of grey granite Ionic columns supporting a raised triangular pediment over an inscription extolling Ludovico Cardinal de Torres. The smaller aisle entrances also have pairs of columns which look like grey marble, but unusually their door-cases are brought forward so that the columns appear as if tucked away on each side. The pediments here are segmental; the three pediments over the entrances are slightly oversized.

These columns are salvage from the 7th century basilica, thrown out in the 1606 restoration. The side entrance ones seem actually to be semi-columns, sawn in half longitudinally.

Over the main entrance is a large rectangular window with a raised oversized segmental pediment containing swags, this over a dedicatory inscription to the martyr. The aisle entrances are surmounted by square windows with Baroque frames and undersized triangular pediments. The nave roofline is dentillated, and there is a dentillated string course below the gable. This gives the impression of a pediment, into which the central window intrudes.

As mentioned, it has been claimed that the architectural details of the façade are early 17th century but that the actual walling is 15th century.

Interior[]

[]

The nave has arcades springing from five very solid longitudinal rectangular piers on each side, with the piers decorated by applied Corinthian pilasters in shallow relief which run up to the entablature below the flat wooden coffered ceiling. The archivolts spring from Doric imposts, and have simple step molding on their edges.

These piers replaced the 7th century arcade colonnades, which featured grey granite Corinthian columns looted from some high-status building such as a temple. It is suspected that some might have been entombed in the piers.

The carved ceiling is unpainted. It has a relief of St Pancras in the middle and the coats of arms of Pope Paul V and the Torres family at front and back flanked by winged putto's heads. In between the portrait coffer and the ones with heraldry are two square coffers containing a tower -a rebus or pun on the name "Torres". The other coffers have Christian symbols and vine-scrolls.

Nibby noted the lack of painting on this ceiling in 1847, and attributed it to Cardinal Ludovico de Torres having died before he could approve the expenditure (he died in 1609).

The interior walls and piers are painted in a cream colour, including the stucco decoration. In the wide frieze of the entablature over each pilaster sits a pair of putti holding swags, and a pair of swags meeting at an angel mask also embellish each of the archivolts of the arcade arches. There is a striking stucco coat of arms of Pope Alexander VII at the apex of the triumphal arch into the transept, with angels as supporters and a rather cross-looking putto holding the mitre.

The counterfaçade has a lavish marble Baroque door-case with a split segmental pediment. Into the split is inserted a bust of St Pancras on a porphyry plinth. The door-case is flanked by a pair of heraldic memorials, that to Cardinal Ludovico de Torres to the left and the other to the right commemorating the takeover by the Discalced Carmelites.

The 13th century Cosmatesque floor of the nave was seriously damaged in the 19th century looting, and was unfortunately ripped up and replaced in the mid-century restoration. This floor was replaced again in 1934, and the present one is of quartzite slabs.

There is a very good quality modern polychrome statue of the Madonna and Child enthroned on the near left hand side, with a pair of rather charming putti in attendance.

Further up on the left is a free-standing ancient ribbed marble Corinthian column with a little angel perched on top.

Losses to the French[]

Looted by the French in 1798, and never recovered, was a pair of highly original and unusual nave ambones or pulpits in Cosmatesque work executed in 1244 and 1249. A drawing of one of them is on the "Romeartlover" web-page, and shows what a tragic loss these were. A sad fragment with derelict Cosmatesque mosaic survives on one of the nave piers.

The French also stripped the church's interior of the polychrome marble which used to decorate it, in the process destroying another central altar which used to be in the nave below the triumphal arch. This had a baldacchino with four columns of porphyry as well, and two of them were fluted. Are they somewhere in France? The position of this altar can be discerned from a fragment of the canopy attached to one of the nave piers, which is in the form of Gothic tracery.

Before the 17th century restoration this altar was flanked by a low screen wall in polychrome stonework and Cosmatesque mosaic, including porphyry panels. This would have functioned to separate the schola cantorum or choir from the main nave area occupied by the congregation in the Middle Ages.

Side aisles[]

The side aisles also have coffered and carved wooden ceilings, and end in a pair of large side chapels which occupy the sides of the transept flanking the sanctuary. These chapels have a large arched portal each, forming a transverse arcade with the central triumphal arch. This architectural feature is original 7th century.

The left hand aisle has a staircase down to "Zone A" of the catacombs, while that down to "Zone B" is between the third and fourth piers on the right.

The aisles have nine white stucco high-relief panels described as being by one P. Lehoux. However, they seem to be in two sets:

One set of four includes certain saints of interest to the Carmelites, and these are labelled: the prophet Elijah, St John the Baptist, St John of the Cross and The Beheading of St Pancras (over his shrine).

The other set of nine are unlabelled, and seem to be just "there". The subjects on view are: The Reception of a Corpse of a Young Man, The Divine Crowning of Two Saints, The Apotheosis of a Saintly Pope and A Martyr in Ecstasy (he is holding a palm branch, and has a beard -not St Pancras?).

These panels are surrounded by painted decoration imitating Baroque aedicules in polychrome stonework. All this work post-dates the 1849 destruction.

Shrine[]

The present relic of the saint is in a 16th century bust reliquary, brought with it from the Lateran treasury. It is kept in an aumbry or glass-fronted cupboard low in the right hand nave aisle, and is only moved to the altar for veneration on his feast-day of 12 May.

Above the shrine is a stucco relief of the saint being beheaded, and in front of it is an ancient column capital with a tablet saying in Italian Qui fu decapitato S. Pancrazio ("Here St Pancras was beheaded"). This is a 17th century pilgrim bene trovato, as any butcher knows that you don't chop meat on stone because you will ruin your blade.

Sanctuary[]

The sanctuary occupies the central part of the transept and the apse. It is raised high above the nave, and is accessed by five steps. Below it is the confessio or devotional crypt that once contained the shrine of St Pancras before he was transferred to under the high altar in the 17th century.

The side walls have frescoes attributed to Antonio Tempesta on the side walls. Each has two saints, with an angel in between them:

To the left, St Pancras is depicted with St Dionysius, who features in his legend. To the right, St Calepodius is depicted with the "other" St Pancras, Pancras of Taormina (he is vested as a bishop).

These works are over original 7th century arcades leading into the side chapels, which have three Corinthian columns each. The columns themselves are ancient spolia, and their imposts are thought to be the re-used column bases from the earlier church built by Pope Symmachus.

The ceiling is painted with the Carmelite coat of arms, and is the only one of the church's six ceilings with paintwork.

The conch of the apse has a fresco by Luigi Ciotti of 1959, showing Christ Jesus in majesty with St Pancras with other saints in front of a field of lilies. Unfortunately, it replaced an anonymous 17th century work which featured putti, caryatids and acanthus scrolls. Art critics have been rather hostile, but actually the style (vaguely early mediaeval) and execution is quite good. However, there are signs of decay already.

On the conch's arch is the relief coat-of-arms of Pope Paul V. This arch springs from a pair of Corinthian piers made to look like grey marble, and the apse wall is decorated as if having framed panels of the same stone. The ancient bishop's throne that used to be in the apse has been lost, and the apse is now occupied by the organ.

High altar[]

The high altar has a baldacchino erected in 1959, using old materials. It is supported by four porphyry columns with gilded Corinthian capitals and bases which stand on grey marble block plinths. These columns support an open square cornice, over which a canopy with four triangular pediments is supported by four corner piers and six little columns on each side. The front pediment contains a little mosaic portrait of St Pancras.

The original set of four ancient columns was looted by the French in 1798, and were recovered after the restoration of papal government in 1815. There seems to be doubt concerning the authenticity of two of them, since only two are on record as having been returned. The back pair seem to be original.

The porphyry sarcophagus below the altar used to contain the lost relics. It has lion's feet legs and applied decoration in gilded bronze, featuring a pair of palm branches (symbolising martyrdom) and the chi-rho symbol.

The sarcophagus stands on a plinth with the epigraph SS. Pancratii et aliorum martyrum ossa, hypogeis olim condita, hic decentius recondita ("The bones of St Pancras and other martyrs, once kept underground, were more fittingly put here"). This refers to the 1606 transfer of relics. The "other martyrs" would have been spurious, mistakenly identified by some alleged symbol on their catacomb burial place such as a palm-branch, a little glass bottle (taken to contain blood) or the letter M.

In front of the altar, the sanctuary platform is cut away and it was here that there used to be a fenestella confessionis or aperture looking into the crypt for pilgrims to view the original saint's shrine. Note that the frontage here is in purple to imitate a looted porphyry slab -it is paint made with haematite.

Cappella del Santissimo[]

Like the relief panels in the aisles, the two side chapels are painted to give the impression of having altar aedicules. This is a sad attempt to make up for the genuine articles looted by the French.

The left hand side chapel is called the Cappella del Santissimo. It now has a large altarpiece depicting St Teresa of Jesus by Palma il Giovane, which the parish is proud of and (2017) is hoping to restore. The depiction is of the same moment of ecstasy which is shown in her famous statue by Bernini in Santa Maria della Vittoria.

The painting replaced a work by Sebastiano Conca featuring Our Lady and St Joseph with St John of the Cross, which was noted by Nibby as being in place in 1847 but was then presumably lost in the 1849 vandalism.

To the left hand side of the altar is an anonymous Calvary in oils which looks 18th century. Towards the left hand aisle is another picture which looks like St Bernard Receiving a Vision of Our Lady -the saint is not in a Carmelite habit.

This chapel contains the Baroque baptismal font, brought from Santi Celso e Giuliano after the parish there was suppressed. It stands in front of the altar, a shallow oval marble bowl with an internal partition. The future Pope Pius XII was baptised in it in 1876, and a wall-monument nearby with a portrait of him commemorates this.

A staircase on the right hand side, protected by a marble balustrade, leads to the confessio.

Cappella del Crocifisso[]

The right hand side chapel is dedicated to the Crucifix, and has modern wall frescoes depicting scenes from the martyrdom of St Pancras in a realistic style. These derive from the same 1959 campaign that produced the apse fresco, but unfortunately have not kept very well. The rain getting in hasn't helped.

There are eight panels. The four on the right feature scenes from the saint's life: Inheritance, Baptism, Condemnation and Execution. On the wall above the entrance arch is Burial and Apotheosis. The wall above the arcade feature two miracles: Threatened Shipwreck in a Storm and Buried Unharmed in a Collapsed Building.

The altar wall frescoes are, however, 19th century work.

Confessio[]

The semi-annular confessio or devotional crypt of Pope Honorius is below the altar. It runs in a semi-circle under the apse, with a passage leading to below the high altar. There are some ancient marble slabs which were originally re-used as flooring when the crypt was dug in the 7th century.

The passage has an altar at the end of it, which looks 19th century with imitation Cosmatesque work around a little polychrome statue of St Pancras. Unfortunately, rising damp has damaged it quite badly. The passage is frescoed to resemble vaguely a catacomb passage, with a curved vault in blue.

Sacristy[]

The sacristy is now a little archaeological museum. It has a collection of Latin and Greek epigraphs recovered from the catacombs, attached to a wall. This seems to comprise most of those found down there. Also on view are remains of sarcophagi and sculptural fragments found in the excavations.

Catacombs[]

Overview[]

There are two sets of catacombs entered from the church. The first is called in modern writings "Zone A", but by archaeologists "Region L". It is down the flight of stairs parallel to the left hand aisle wall. The second is "Zone B" or "Region M", down a steeper set of stairs between the third and fourth arcade piers to the right.

The catacombs are much more extensive than these. Two other regions are described as accessible: "Region K" to the left had side of the sanctuary and "Region N" under the convent.

Only part of "Region M" is accessible under the contemporary (2017) parish scheme for tours in return for charitable donations. Other regions will come under the Rules Regarding Visits to the Catacombs Closed to the Public, and visiting is under seriously restrictive conditions.

For an overview of catacombs in general, see Catacombs of Rome.

Region L[]

The area with its entrance in the left hand aisle was named in the 17th century after Octavilla (Ottavilla) who features in the legend of St Pancras, and who was probably the owner of the graveyard in which he was buried. Visitors then were told that the martyr was enshrined here, but that is now doubted.

There is a complex network of galleries with loculi, bearing witness to much patching and re-use since early times.

Region M[]

The part you can visit consists of part of Region M. The rather awkward entrance staircase leads to a set of passages on two levels with several cubicula or private rooms. The dimensions of the passages are smaller than those of the more famous public catacombs such as the Catacombe di San Callisto.

There are three important cubicula: one containing a tomb of someone called Botrys Christianos (literally meaning "Christian bunch of grapes"), one named after St Felix which has paintings of ships and fish and, most importantly, one called "Cubiculum 13" with four floor-tombs which was venerated in the Middle Ages as the shrine of SS Sophia, Fides, Spes and Caritas. These were meant to be martyrs, a mother and three daughters called Wisdom, Faith, Hope and Charity.

The Botrys Cubiculum and Cubiculum 13 are perhaps the earliest part of the entire catacombs, and are thought to have been independently excavated as private hypogea in the very late 3rd century -about the time when St Pancras was martyred.

Region N[]

Region N, under the convent (that is, to the right of the church) is a warren of passages which is also considered to have been a consolidation of several previously independent excavations on two levels. The so-called "area G" contains a cubiculum which has been tentatively identified as a martyr's shrine owing to alterations made apparently to facilitate access.

This region is 4th century.

Region K[]

The last region is apparently accessed through an outside entrance, somewhere on the other side of the door on the extreme left of the church façade (the writer would like to have this confirmed). It consists of four galleries arranged crosswise, and contains frescoed cubicles as well as devotional graffiti giving witness to mediaeval visitors.

Apparently a connection existed between this region and Region L in the 16th century, when the catacombs were being explored again. However, there have been passage collapses since which have not been sorted out.

Access[]

Church[]

Owing to its being some distance from the Centro Storico, this church now gets few pilgrims and fewer tourists. As a result, it is no longer open all day. The times are from the parish website, July 2018.

Weekdays 09:00 to 12:00, 16:00 to 19:00. (From July to September the afternoon closure has been at 19:30.)

Sundays and Solemnities 8:00 to 13:00, 16:00 to 20:00.

The walk from Porta San Pancrazio is not a short one. The 44 bus from Piazza Venezia passes close by (get off at Ottavilla/Pamphilj).

Catacombs[]

The parish should be congratulated on re-opening part of the catacombs to visitors.

Guided visits are given to groups, the maximum in a group being twenty. These take place on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays at 9:30, 10:30 and 11:30. On Wednesdays only further tours take place at 16:30 and 17:00.

The tour is given gratis, but those taking part are urged to donate either money or foodstuffs to a charity helping poor people in the city. Please be ready with your donations on arriving.

The parish website advises that visits at other times can be negotiated with the Parish Office.

Liturgy[]

Church[]

Mass is celebrated (parish website, July 2018):

Sundays 8:30, 10:30, 12:00, 17:30 (not July to 2nd Sunday in September), 18:00 (19:00 ditto).

Weekdays 7:30 (not July to 2nd Sunday in September), 9:00, 18:00 (19:00 ditto).

The Rosary is recited on Mondays to Thursdays at 17:30, before the evening Mass.

There is Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament on Fridays at 17:00 until the evening Mass.

Other places of worship[]

The parish contains another convent church:

Santa Maria della Consolazione a Piazza Ottavilla, under the charge of the Discalced Augustinian friars.

Also, there is the former convent chapel of Santa Giuliana which amounts to a church edifice but has a very uncertain future.

Neither of these is a parish Mass centre.